On July 20, 1969, my brother, and I were with our parents in a real-life Fawlty Towers on the banks of Lake Como in Northern Italy.

I was a perennially annoyed thirteen-year-old looking forward to this long road trip from Paris to Rome with my parents to be over, not fully appreciating the sights and experiences along the way. This wasn’t a dream vacation.

This was us visiting my mother’s family in Italy, while we lived in France for the years my American father would be working in the Paris office of United Aircraft Corp. We’d be doing it all again the next summer, and the next.

We had been uprooted the year before from our Connecticut home and sent to Europe. My eleven-year-old brother and I missed our friends, being able to watch TV in a language we could understand, and being able to find vanilla extract in the grocery store. (Why do European cookies taste different from American cookies? No vanilla extract.)

Being the children of an aerospace engineer, we heard discussions of the Space Program all the time. The achievement of humans traveling to the moon and back was part of normal life for us. Of course it was going to work. We had the technology, and the entire country was working on it. You know the look on the face of an eleven-year-old today when they have to show grandma how to use Instagram? That was my brother and me.

So it was to our vague surprise that the hotel manager called every human in the building to the lobby early of the morning of July 21. We gathered around a small black and white television set on a tiny table. As the realization spread through the room that my family members were the only Americans in the hotel, we were shuttled to the front for the best viewing.

There was silence as we watched, then cheers, and a lot of handshakes and pats on the back. One would have thought my entire family worked for NASA. At that moment, my family represented the whole of the United States of America. To the group in the hotel, we were heroes.

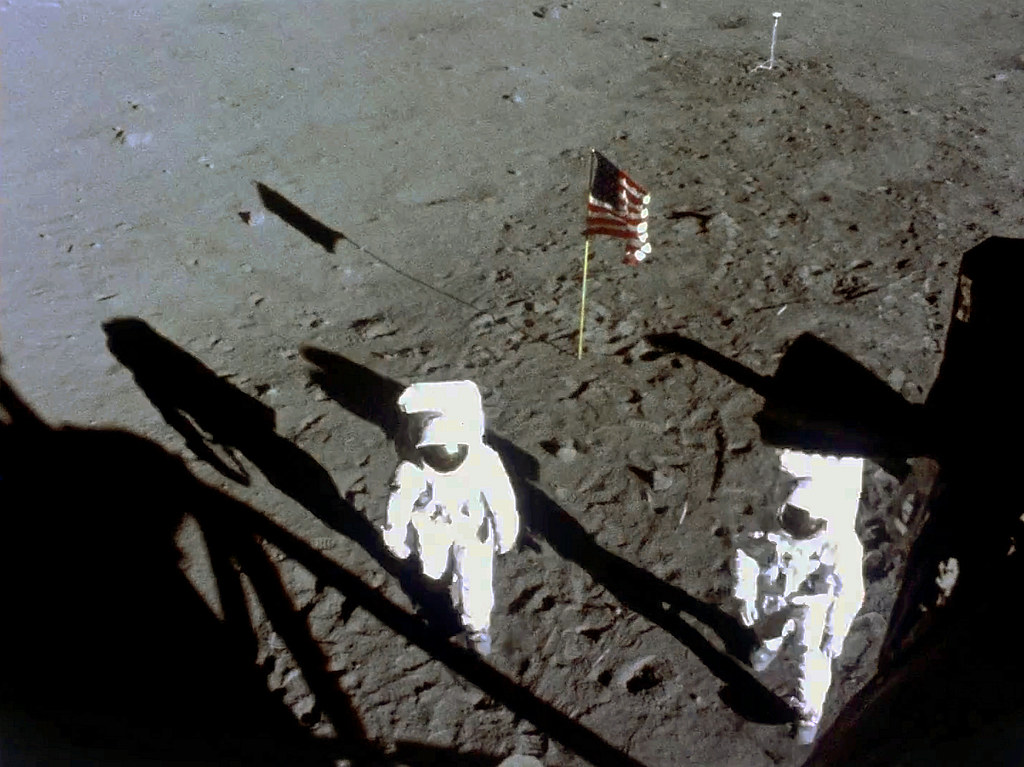

The fuzzy images on the television screen of the astronauts stepping onto the lunar surface jolted me out of my teenage ennui. There were humans on the moon. More incredibly, we got to watch it happen across that vast distance of space. Even more incredibly, they were going to hop back in their machine and fly back to Earth.

From then on, things would be different. We proved we could go anywhere, do anything. There would be a moon base in no time; travel between the two rocks would be commonplace. We were going to cure disease and poverty and end all wars. We had the technology. We believed in science. And the world looked to us as heroes.

OK, so, a lot of things have, and have not, happened over the fifty years since. I’m now the one who pulls up NASA TV on my computer screen at work to watch SpaceX rockets take off. I’m the one wondering why no one else in the office seems to think this is significant enough to interrupt the day. Humans in space have become commonplace.

Belief in science, however, not so much. Reliance in current science, yes, when we need it; when we are at the doctor or have to go somewhere in a car or wonder why we didn’t detect listeria in our lettuce before it hit the store shelves.

Consider the science that’s going to save us from the climate crisis, cure Ebola, and clean the oceans. Do we have enough faith to put in the money, time, people, and energy needed, like we did when we were racing to the moon?

Let’s aim to be heroes again. Closing our doors to the rest of the world will not move us forward. We need to put aside the tribal bickering and come together for the common cause of saving the planet. We need to put scientists and engineers in charge of the science and technology. We need to give them the respect and resources they need to do the job we need them to do.

We did it once; we can do it again.